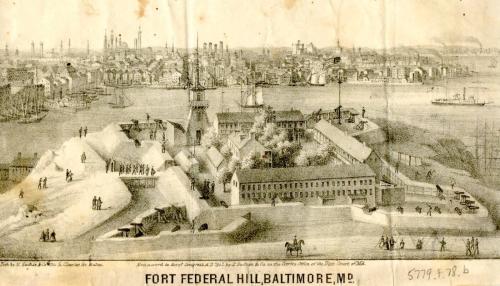

Bird's-eye view of the enclosed fort on Federal Hill overlooking the Inner Harbor. Courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia.

Divided Border State

On the political struggles and question of enslavement that led to the Civil War, Maryland was a divided state. Baltimore was the largest industrial city in the South and the third largest city in the country. Agricultural interests in Southern Maryland and the Eastern Shore favored enslavement and the South. Central and Western Maryland tended to ally with the industrial North and view enslavement as either economically unviable or morally wrong.

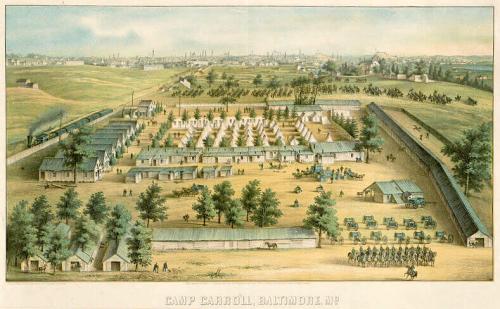

Camp Carroll

After a pro-secessionist mob attacked federal troops in Baltimore in April 1861, more federal troops moved in to occupy the city. That summer Camp Carroll was established on Mount Clare’s western pastures (today’s Monroe Street and the Montgomery Park parking lot) to provide a cavalry training ground, and to protect the vital rail link between Washington, D.C. and the North. The Camp hosted a total of 17 units, many for short periods of time. New recruits were often ill-equipped during their brief stay at Camp Carroll waiting for equipment and orders.

"…and a motley looking crew we were, without uniforms. The country boys in their home-spun clothes, others in their working clothes, the dude in patent leather shoes and Piccadilly collar, the farmer and the blacksmith, altogether it was typical of the make-up of that Great Union Army."

Frederick W. Wild, Memoirs and History of Captain F.W. Alexander’s Baltimore Battery of Light Artillery U.S.V.

Baltimore mapmaker E. Sachse & Co.’s 1862 birds-eye view of Camp Carroll. Mount Clare mansion is in the back, right corner amongst the trees. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

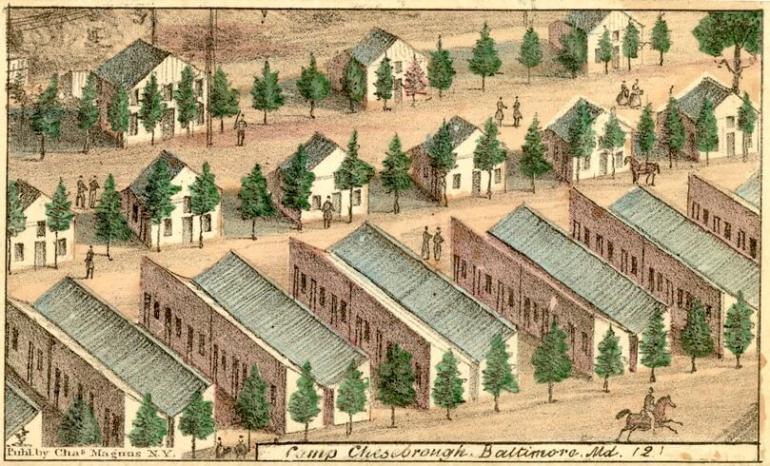

Camp Chesebrough

In 1863, the Connecticut First Cavalry rebuilt the camp with permanent structures and changed the name to Camp Chesebrough to honor one of their leaders. The name reverted back to Camp Carroll when the First Maryland Veterans Volunteer Calvary returned in March 1864.

Assembly Place

Mount Clare, physically separated from the camp, remained a hotel or boarding house during the war. However, the house served as an assembly place for the community, especially for the “patriotic ladies of West Baltimore” to honor the officers for their service.

Mount Clare's outbuildings suffered grave damage and neglect during the war. The western wing housed a jail. Other dependencies may have been used for additional housing or deconstructed to burn as fuel.

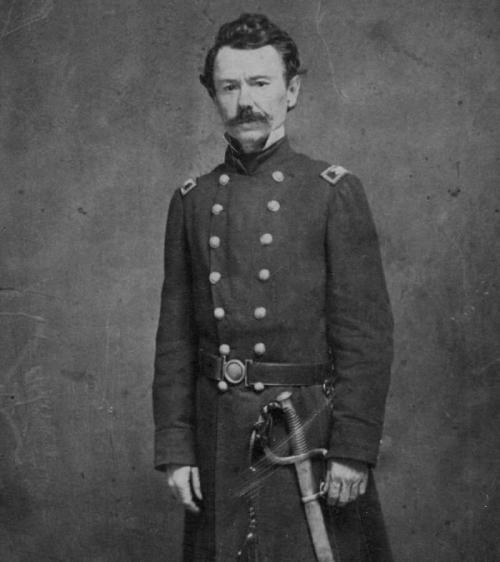

Baltimore attorney and Mexican-American War veteran John R. Kenly was the first Commander of Camp Carroll. He was promoted to Brigadier General by the Civil War’s end. Public domain image.

"A remarkable feature of the occasion consisted in the fact that a very large proportion of those present were ladies. The regiment being formed, a bevy of young ladies, thirty-four in number, each representing a State, and dressed in white, wearing a beautiful floral wreath upon their heads, and preceded by several gentlemen having the flag in charge, advanced between the lines, and marched up in front of the old family mansion, it was said, was once occupied by General Washington.

Colonel Kenly concluded by placing upon the neck of the fair representative of the donors a wreath of beautiful flowers, when the ladies in attendance sung “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and the band struck up the “Gay and Happy Quick Step".

The ceremonies ended with the singing of other patriotic songs, some of which were written for the occasion, when, after some fine music from the band, the line was dismissed, the companies proceeded to their tents, and the vast assemblage returned to their homes."

Describing the presentation of a standard to Colonel John R. Kenly, Commander of Camp Carroll, by the patriotic ladies of West Baltimore. By Charles Camper and J.W. Kirkley, Historical Record of the First Regiment Maryland Infantry.

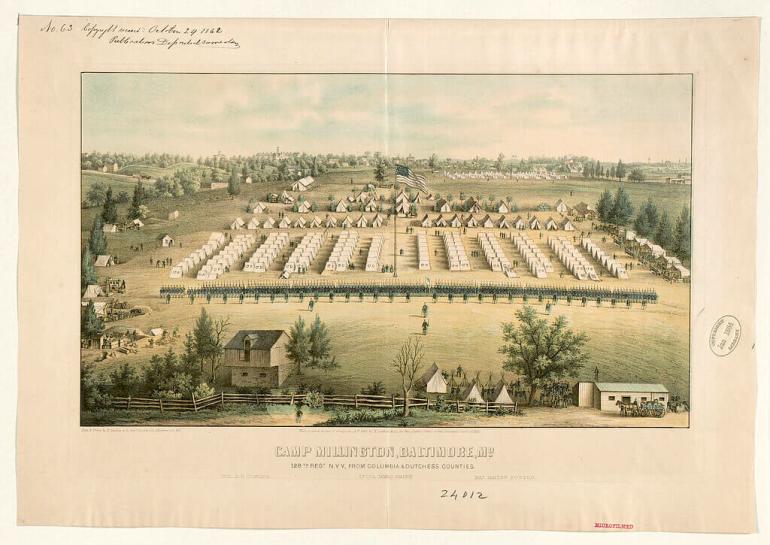

Camp Millington

The Carroll’s former plantation hosted a second Civil War camp named Camp Millington. An infantry training camp, it lay east of Gwynn’s Falls near the Carroll’s upper Millington Mill (today between Brunswick Street and Millington Avenue.) Volunteers from New York state’s Columbia and Dutchess counties built the camp.

Veteran Reunions

After the Civil War ended, several state and local organizations were formed to support civil war veterans. The Grand Army of the Republic, (GAR) founded in 1866, emerged as one of the most powerful veteran fraternal and lobbying organizations. In 1868, the GAR was instrumental in establishing Memorial Day as a national observance for American war dead. One of the first integrated fraternities, the GAR accepted Black members and initially supported federal voting rights for Black veterans.

The GAR held national and statewide encampments or reunions. Mount Clare’s grounds served as the encampment site for at least one reunion in September 1884.

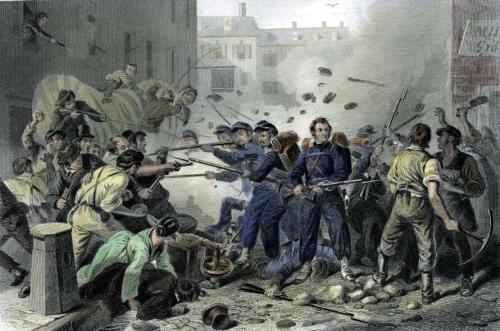

Massachusetts Militia being attacked by pro-secessionist Marylanders during the Baltimore Riot. Engraving by F.F. Walker, 1861. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

The Baltimore Riot launches Clara Barton

Attempts to assist some of the first victims of the Civil War propelled Clara Barton, a former Massachusetts teacher living in Washington D.C., to lay the foundations of an international relief movement. On April 19, 1861, the Sixth Massachusetts Volunteer Militia arrived by train to Baltimore and began marching through the city to continue their journey south. Enroute, they were attacked by a mob of Southern sympathizers in what came to be known as the Baltimore Riot. When the wounded troops arrived in Washington, D.C., Barton recognized many of the soldiers as former students or family friends. She quickly organized donations of food, clothing, and medicine for the wounded who were being housed in the unfinished U.S. Capitol. She also offered the young men emotional support, reading, writing letters, and chatting with them as they convalesced. These volunteer efforts launched Barton’s relief work that culminated years later in her founding and leading the American Red Cross.