View of quarters of enslaved workers on Mulberry Plantation, in South Carolina, by Thomas Coram, c. 1800. Courtesy of Gibbes Museum of Art, Carolina Art Association, Charleston, S.C.

Resistance and Resilience

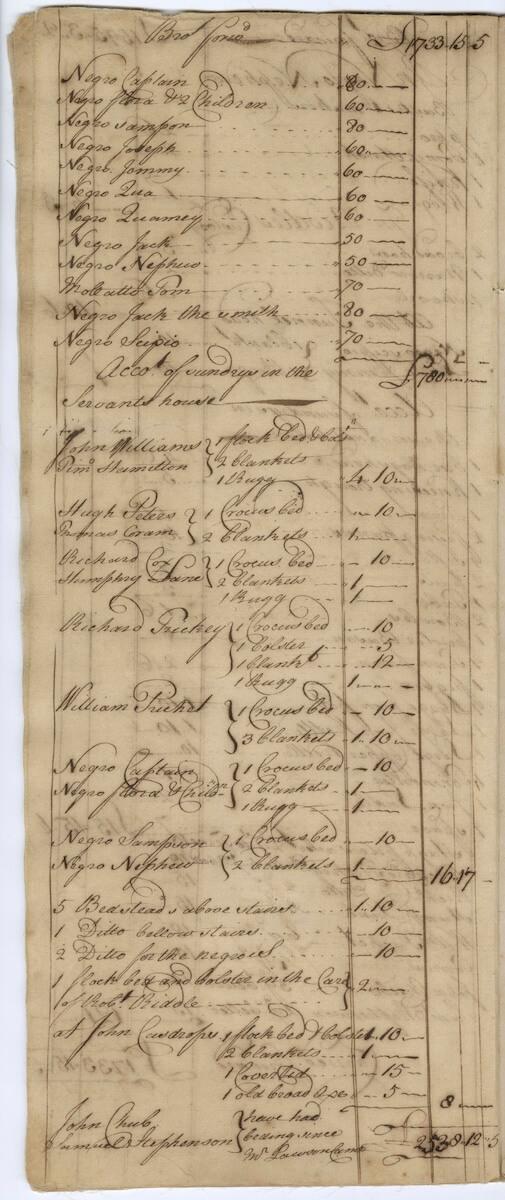

The enslaved people held by the Carrolls were not complacent. Many resisted in large and small ways. Some worked slowly or clumsily, and others sought their freedom. Some demonstrated their resilience by mastering their jobs and earning privileges. At the Baltimore Iron Works, an overwork system allowed workers, including the enslaved, to earn credit at the company store.

The enslaved, many of whom were kidnapped from the West Coast of Africa, brought with them knowledge of farming, cattle herding, boat building, architecture, weaving, and much more. Many enslaved transitioned from unskilled workers to highly skilled craftsmen.

"I would have the Kitchen (roasting) Jack made of the Sort Least Liable to be out of order as our Negro Cooks and Servants are but Careless and Rough Handlers of anything that may be Trusted to their Care."

From a 1765 letter from the Barrister to his English agent

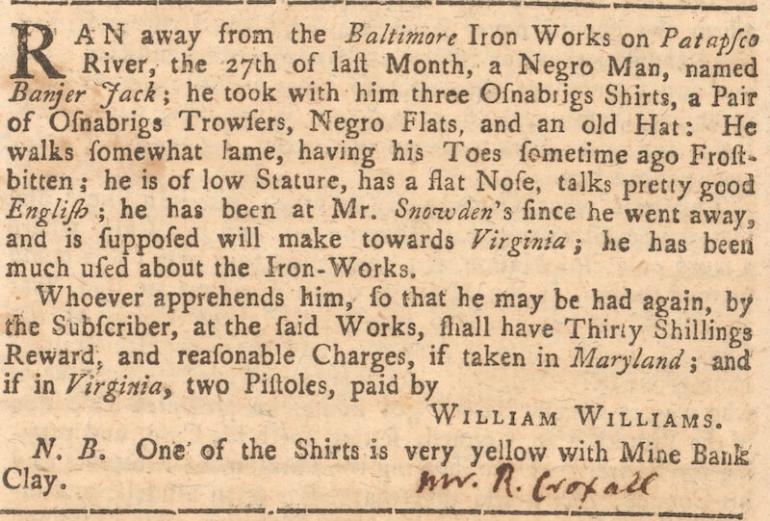

Maryland Gazette classified ad seeking the return of Banjer Jack, an enslaved man who sought his freedom from the Baltimore Iron Works in 1751. Courtesy of the Maryland State Archives.

Manumission

Manumission laws were designed to protect the public from destitute free persons and ensure that slave holders did not evade responsibility for their elderly enslaved. Freed blacks had limited job prospects. In Baltimore freed men could work in the maritime trades, as brick makers, bricklayers, shoemakers, tailors, artisans, field hands, or laborers. Women could only find jobs as housekeepers, washerwomen, seamstresses, cooks, or nannies.

Margaret Tilghman Carroll planned upon her death to free the 49 enslaved people who lived with her at Mount Clare and The Caves, but charged her executors, two nephews, with working out the details.

Family Separation

Only nine adults and six children were freed shortly after Margaret’s death in 1817. Thirty-four people were resold under delayed manumission, meaning they would be freed once they reached a certain age, often between ages 28 and 36. Only 23 officially registered as free.

Margaret’s executors separated each of the four large families who lived at Mount Clare and The Caves. Of the 13-member Garrett family, four were freed, and nine others were sold to six different slave holders. The 11-member Lynch family saw five people freed and six people were sold to three different slave holders. Children as young as six-years-old were sold away from their parents and siblings.