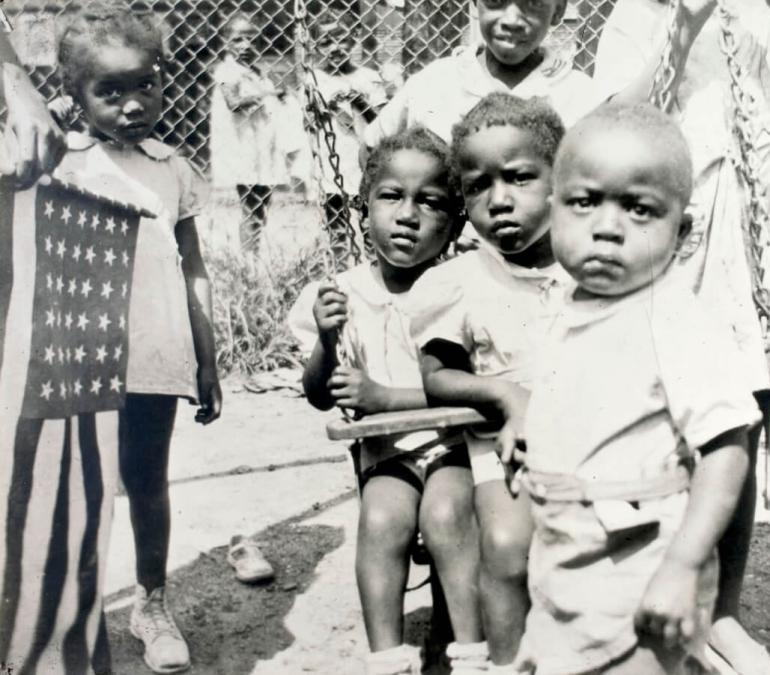

Carroll Park playground, 1909. In segregated Baltimore it was only open to white children. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Public Park – Carroll Park

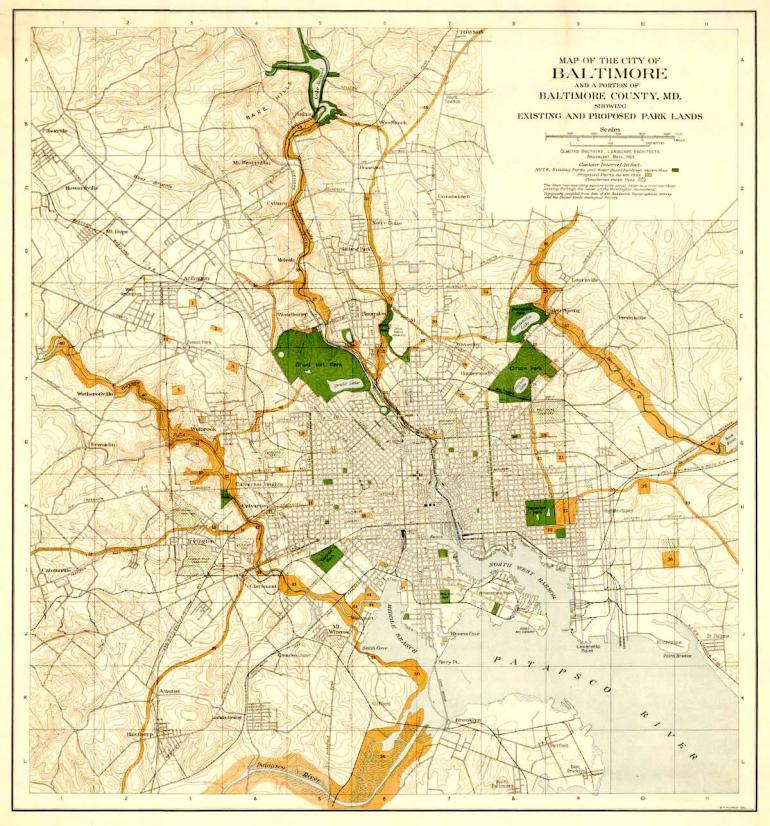

At the end of the twentieth century, a new approach to urban planning emerged called the City Beautiful Movement that encouraged greenspaces in overcrowded cities. In 1890, Baltimore City purchased Mount Clare and surrounding land from Carroll heirs for $45,000 to create a city park. The city pulled down many of the Schuetzen-era buildings, including the kitchen wing. However, the former plantation still bore the scars of its industrial past, with gaping pits and stagnant, dirty ponds from the earlier clay mining operations.

Green Corridors

Development of Carroll Park was sluggish until wealthy Baltimore residents formed the Municipal Art Society in 1899 to beautify the city. In 1902, the Society hired the Olmsted Brothers, whose father designed New York’s Central Park, to develop a comprehensive park plan. The firm envisioned a network of green corridors that followed Baltimore’s three major stream valleys and linked existing parks.

Museum

For Carroll Park, the Olmstead Brothers designed a plan to preserve Mount Clare and offer a mix of active and passive recreation incorporating ball fields and formal gardens. In an attempt to restore the house’s colonial architecture, the city built Mount Clare’s current wings and hyphens in 1908. Briefly, the home served as the Park Director’s residence, but by 1917 the city had turned Mount Clare over to the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in the State of Maryland to create a colonial house museum. The new wings were used initially as offices, but were quickly transformed into public bathhouses for the park. In 1959, the bathhouses were finally closed and by 1960 the wings were incorporated into the museum.

Organized Play

At the turn of the century, Baltimore reformers began to view organized recreation as a way to improve the health, education, and morals of its poverty-stricken youth. Two pioneering feminists, Eliza Ridgley and Eleanor Freeland, founded the Children’s Playground Association in 1897 to create safe playgrounds in school yards and public parks. According to founding documents, there were only two playground rules, “be kind to one another and have clean faces, hands, and feet.”

The same year, Robert Garrett, an heir of a prominent Baltimore banking and railroading family, established the Public Athletic League to foster rigorous sports competition, primarily for boys. Garrett was the gold medal winner of the Discus and Shot Put events at the first modern Olympics, held in Athens, Greece, in 1896 and an avid proponent of organized sports.

Separate and Unequal

From their inception, both organizations maintained separate and far from equal programs for white and black children. By 1907, the Children’s Playground Association had built 28 playgrounds, but only seven were open to African Americans. In 1922, these two groups merged to form the Playground Athletic League (PAL), which had primary jurisdiction over Baltimore’s playgrounds and parks until 1937. In 1940, the city formed a new Department of Public Recreation by consolidating PAL and several other private sports groups. The new department was administered by a 7-member Park Board appointed by the Mayor.

By a “routine and long-established” policy, the Park Board banned interracial play in all their facilities. Ball fields were allocated on a first-come, first-served basis unless reserved. Police were ordered to break up games between white and black youths.

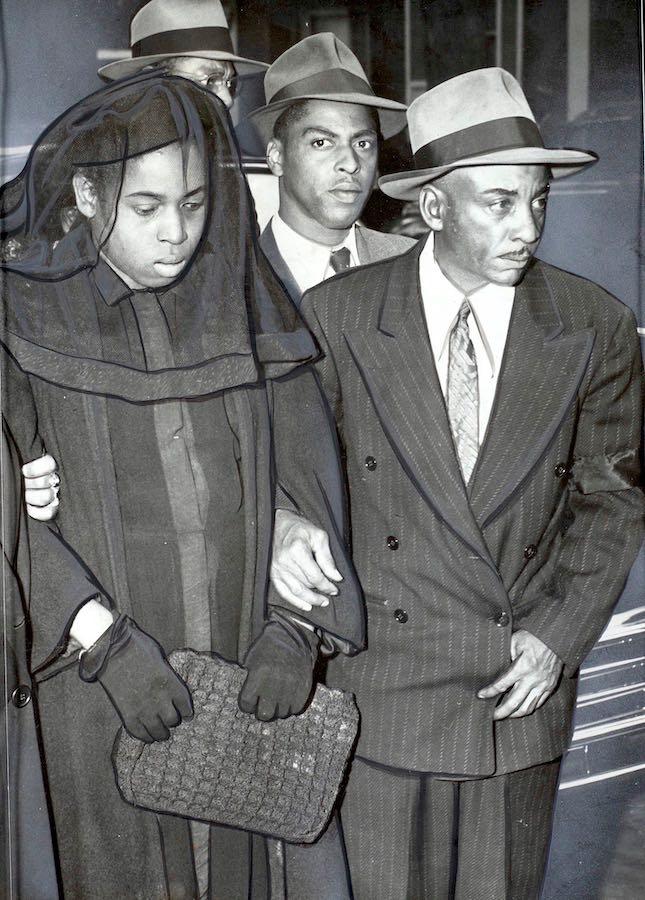

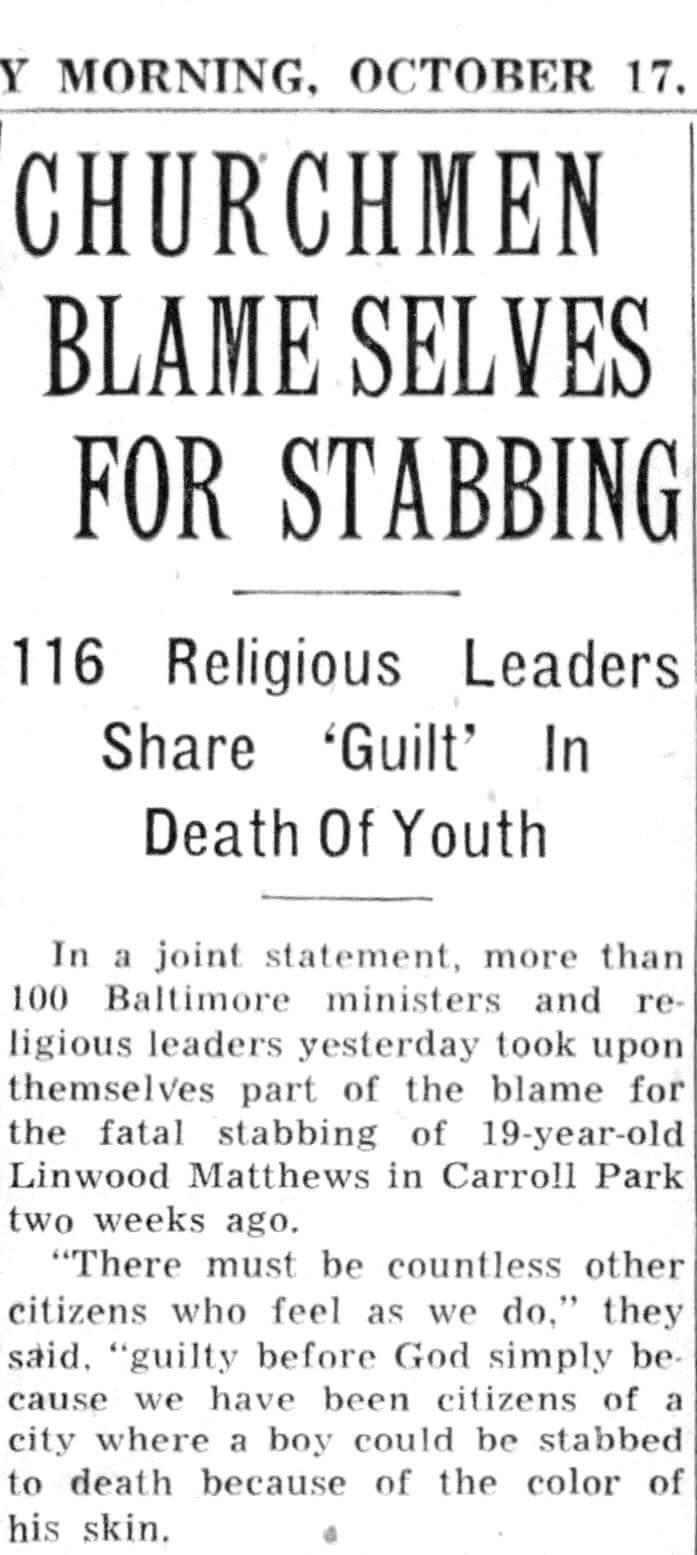

Murder in Carroll Park

The policy banning interracial play had fatal consequences on Oct. 2, 1949, when Linwood Fleming Matthews, a 19-year-old African American, died from a stab wound he received in Carroll Park during a clash between white and black teens. The stabbing occurred when a group of black teens returned to the park armed with sticks after having been chased away by white teens. An 18-year-old white youth was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to five years for Matthew’s death.

Board Fails to Act

Sensing the potential for public outrage at the murder, Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro convened a special, closed-door session of the Park Board the next day to thoroughly investigate the tragedy. The first and only black member of the Park Board at that time, Dr. Bernard Harris, a surgeon at Provident Hospital, blamed the Board’s segregation policies for instilling the idea that certain parks were for certain races. Police and community members said the Board’s rules fostered a climate of racial hostility.

Supreme Court Forces Change

At the trial of the defendant, prosecutors denied that the murder had racial overtones, and referred to the stabbing as “as just another fight” between “two bad boys.” It wasn’t until five years later, following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, that the Park Board officially ended segregation in all its facilities.

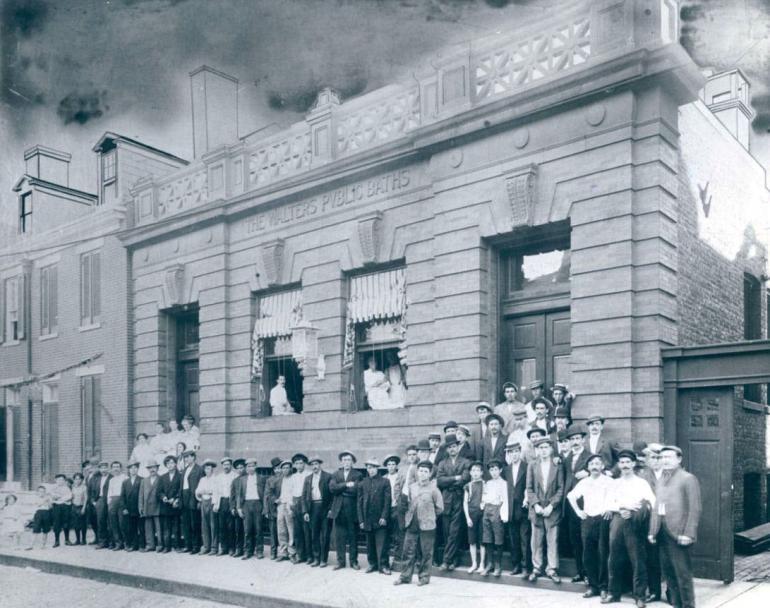

Children outside the public bath house at Patterson Park who have not yet learned to bathe regularly, August 1916. Photograph by Harry B. Leopold, courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Public Bathing Facilities

As crowded, dirty slums proliferated in big cities at the turn of the 20th century, social reformers promoted the concept of regular bathing to bolster personal dignity and prevent disease. Baltimore’s first initiative - a public bathing beach established in Canton by the Congregational Church’s Rev. Thomas M. Beadenkopf in 1893 - proved to be only a warm weather solution. Railroad Magnate Henry Walters agreed to underwrite construction of five public bathhouses that were administered by the city’s Public Bath Commission. Only one, Walter’s Public Bath House No. 3 on Argyle Ave., was open to African Americans.

Schools and Parks

The Commission successfully lobbied for the inclusion of public bathhouses in schools and public parks. By 1939, the Public Bath Commission was offering free bathing in six bath houses and 27 public schools. They also ran 14 portable showers during the summer months. The Department of Recreation and Parks oversaw several more bathing facilities in the city parks and pools.

Children wait their turn at the “Whites Only” public baths in Patterson Park in August 1916. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Obsolete

Attendance at the baths began to decline in the early 1950s. New housing regulations required that every dwelling have a bath or shower by 1956. Baltimore’s last public bathhouses closed in 1959, including the ones at Mount Clare.