Rifle range at the East Baltimore Schuetzenhof, lithograph by Hunckel & Sons, 1858. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

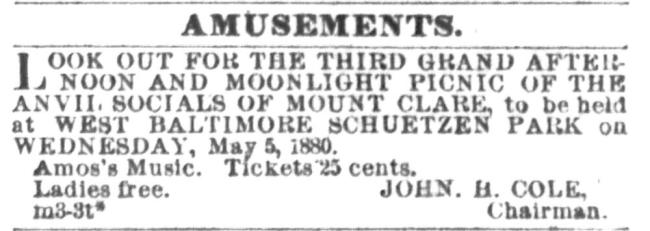

Private Park - West Baltimore Schuetzen Association

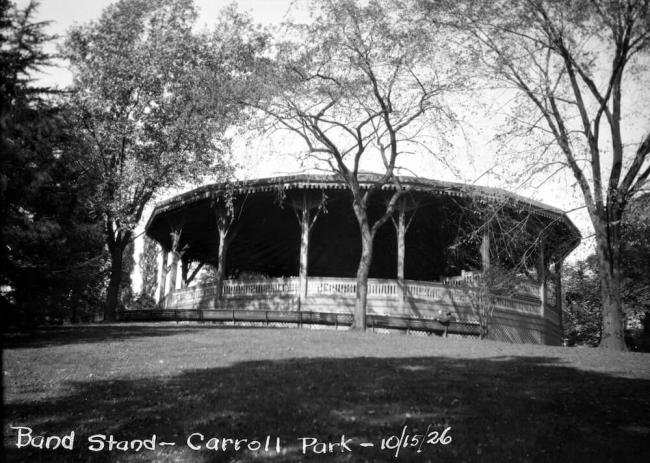

Baltimore saw huge influxes of Irish and German immigrants in the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1870s, a quarter of Baltimore’s residents claimed German heritage. These immigrants influenced the cultural life of the city with German language newspapers, schools, and social clubs. One group, known as West Baltimore Schuetzen Association, leased Mount Clare and 15 surrounding acres for use as a private club beginning in 1871. They built a shooting range and bandstand, hosting marksmanship competitions, moonlight picnics, and dances. They leased the property from Carroll heirs for $800 per year.

The Schuetzen Association used Mount Clare as their clubhouse, turning the dining room into a beer hall, and the parlor into a dining room. With permission, they demolished Mount Clare's dilapidated wings and dependencies in 1873 and built a new, two-story kitchen. But by 1886, the Schuetzen Association had given up its lease.

Driving Force

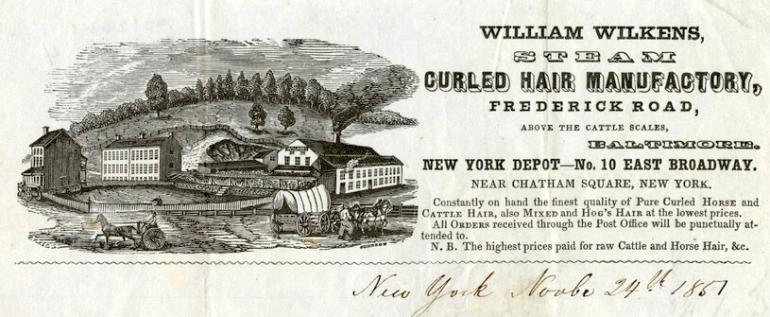

A leading Baltimore citizen instrumental to opening the West Baltimore Schuetzen Park at Mount Clare was William Wilkens, a German-born entrepreneur. He began an animal hair processing business in 1843 that used hair from horses, hogs, and cows as stuffing for mattresses and upholstered furniture. The business prospered and by 1845 Wilkens built a large factory on Frederick Road. The factory reputedly emitted a terrible odor and, like the surrounding businesses, dumped waste into Gwynns Falls stream. Wilkens Avenue is named after him.

In 1849 the B&O extended its tracks to the deepwater port at Locust Point where ship passengers and freight could be transferred directly to trains. Lithograph by J.D. Ehlers Co. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

German Immigration

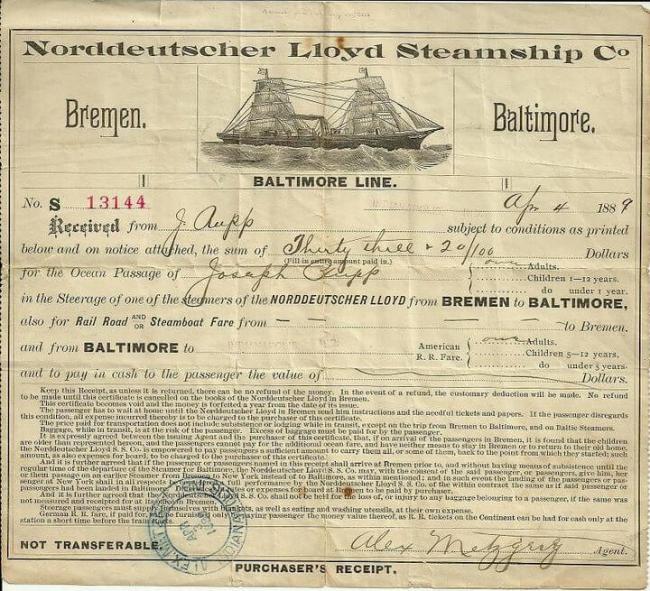

The trickle of German immigration to Baltimore became a wave in 1848 in the aftermath of political uprisings in Europe. Beginning in 1868, a partnership with the North German Lloyd (Norddeutscher Lloyd) shipping firm brought passengers by steamship from the German port of Bremen to Baltimore’s Locust Point Pier, where they could immediately board B&O trains heading west. Transatlantic crossings by steamship took about three weeks, cutting by more than half the six-to-eight weeks required for sailing.

The S.S. Baltimore

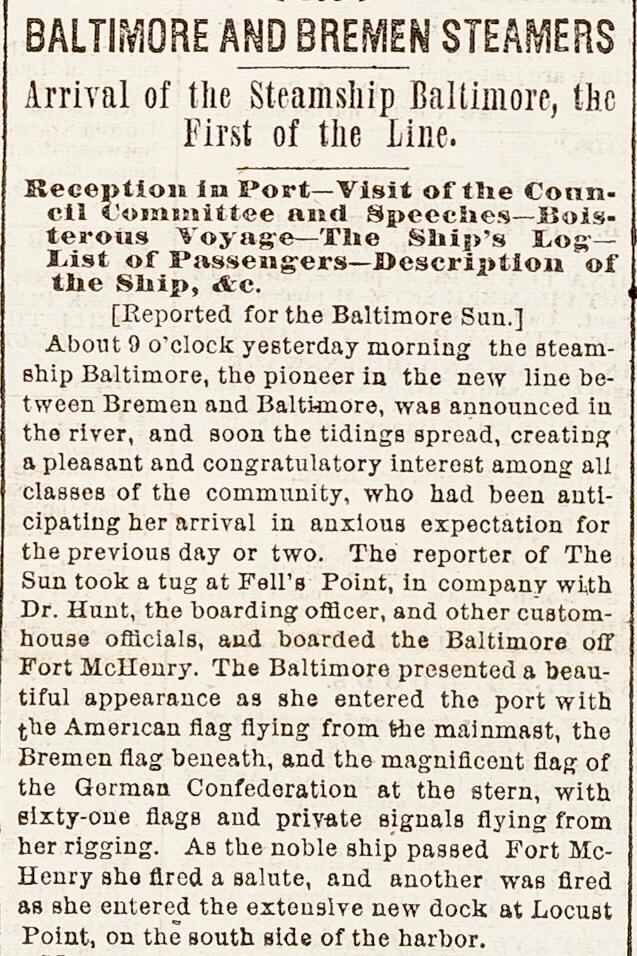

Baltimore’s role as a North German Lloyd destination placed the city on the cutting edge of the country’s communication and transportation network. It meant a European steamer would arrive and depart every two weeks through South Hampton, England, bringing news, passengers, and products. The S.S. Baltimore, an iron steamship built in Scotland, opened the Bremen-Baltimore line with its maiden transatlantic voyage on March 3, 1868. Her arrival on March 23, two days late, was marked by a city-wide holiday, parade, and three-day celebration.

"Baltimore, by these means, can be placed in a position to realize all her geographical advantages, and thus prepare to accomplish the great commercial destiny that awaits her. Her business and connections can be rapidly increased and developed, and in time her great natural advantages, combined with proper energy and enterprise on the part of her citizens, will cause her to rank in the very first class of the commercial cities of the world."

Baltimore Sun on the city’s bright future with the opening of the Bremen shipping line along with planned interstate road and rail construction. February 13, 1868

Newly arrived immigrants separated into pens according to their destinations on B&O trains at Locust Point Pier, June 14, 1904. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.