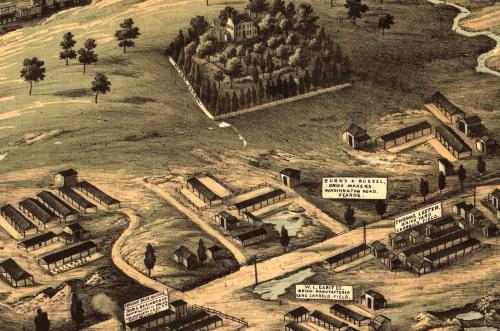

Detail from the brickyards at Mount Clare from the 1869 E. Sachse & Co. bird’s-eye view of Baltimore map. The house is in the fenced enclosure at the top center. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Brick Making

Clay, another abundant raw material in the Baltimore region, sparked a brick-making industry that eventually gained international acclaim. During the 19th century, Baltimore was riddled with clay pits and brickworks.

Most of the bricks used to build Mount Clare were likely made onsite. While a 1759 invoice shows Mount Clare’s owner, Charles Carroll, Barrister, purchased 500 bricks from a Baltimore merchant, more were needed to complete the house. The Barrister likely hired a gang of brickmakers, made up of enslaved and paid workers, who built a kiln at the building site and dug clay from the surrounding fields. They also would have used local mortar made from oyster shells and marl, a dense mineral mud.

Clay Mining

James Maccubbin Carroll, the Barrister’s nephew who inherited Mount Clare and its grounds-known as Georgia Plantation- embraced the industrialization that was encroaching his property. In 1827, he began leasing a large meadow known as Carroll’s Field to various brick manufacturers. Carroll descendants continued to rent out these fields until the clay was depleted in 1875.

Carroll’s Field Brick

More than 85 million bricks were produced from Carroll's Field clay over nearly 50 years of mining. An estimated 80 percent of homes west of Jones Falls stream are believed to contain Carroll’s Field brick, as well as the Phoenix Shot Tower, Baltimore’s Old St. Paul’s Church, and the original buildings of U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis.

Burns & Russell Co.

One of the main brick manufacturers leasing Carroll’s Field was Burns & Russell Co. It operated more than 25 fields throughout the city including clay yards in present-day Ravens and Orioles stadiums. It also supplied brick to the B&O railroad for all their tunnels, stations, and the Camden Yards warehouse. Russell Street was named for the company’s founding family. The company, now called Spectra Development Corp., still makes masonry products today.

International Acclaim

During the 1870s, Baltimore brickmakers garnered a worldwide reputation by taking top honors at international building expositions. Renowned architects, including New York’s McKim Mead & White, requested Baltimore brick for their commissions. Wealthy captains of industry, including Marshall Fields of Chicago and Cornelius Vanderbilt of New York, insisted on Baltimore brick in their homes.

"They are distinguished for their perfect shape, clear-cut edges, smooth surfaces and color. They have a permanent cherry-red color that does not fade or become stained by the action of the atmosphere or rains."

Description of Baltimore-made bricks from The Monumental City, It’s past History and Present Resources, 1873.

The “Great Baltimore Fire” destroyed more than 1,500 buildings in the heart of the city. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Loss of an Art

In the construction boom following the “Great Baltimore Fire” of 1904, demand for building materials skyrocketed. Newly-developed machines could mass produce bricks more quickly and cheaply than making them by hand. The art of hand molding bricks was lost as skilled craftsmen were replaced by machines.